Technical Debt frfr

- … ‘technical’ debt?

- Still not convinced?

- But wait, there’s more!

- So in conclusion… (where the heck is he going with this??)

… ‘technical’ debt?

One of the most confusing things I came across in my early and mid years as an engineer was the answer to the question “What exactly is technical debt”? Go ahead, think about the answers you’ve been given. I’ll list a few cliche’s I’m sure we’ve all heard:

- “Ehh, that code is old. It’s just debt that needs to be paid down"

- "Jerry wrote that. We need to refactor it, so make a ticket and throw it in the debt backlog” (Narrator: They never wrote that ticket.)

- ”We can’t add another pattern to this project. This is how we get debt.”

None of that really made sense to me. Sure, ‘legacy’ code that you (did or didn’t) write is always derisively spoken of. That doesn’t make it debt though. Debt is something borrowed, owed, or obligated to. It also typically creates more of itself (exponentially). I went on a crusade to actually define what it actually was.

”Deliberate” kept coming up in my searching and reading. I started to see a pattern forming. Among most of the ‘accepted’ definitions (read: highly commented on blogs, trusted industry thoughts) this was the most common adjective. Makes sense right? Predatory lending aside (a whole other topic I’d love to wax philosophical on…), debt is usually accrued knowingly. Very few people can afford houses outright, but everyone needs a roof over their head (which is a topic for yet another day), so folks take on debt to pay back over time, or, they end up renting a space which can feel like debt. The point is: this was an intentional or deliberate borrow.

So how does this relate to technical debt? Well, my definition of ‘true’ technical debt is code or architecture “taken on deliberately or intentionally, to ship software faster”. Some examples you say?

- ”We can just hard code these lookup values in the provider classes. They’re bound to change, but we can at least get this feature shipped sooner to get feedback on if we even want to go wide with it."

- "I don’t love having to maintain two different implementations of the same feature, but we need to know which path truly performs better in the wild before we can make the long term decision.”

Here are some common scenarios that I believe strongly are not technical debt:

- Junior dev who doesn’t know any better develops a pretty brittle feature. Mid level dev comes in 6 months later and laments about all the bad code and debt there.

- In reality, shame on the mid level dev for missing a coaching opportunity during the original PR!

- An engineering team wants to migrate their legacy web app (developed in say… knockoutjs) to a more modern front end. There have been a couple attempts over the last year with frameworks that never quite got to the finish line for one reason or another. Now, there are a few pages written in angular, some components in blazor and whole companion site in the same monolith repo developed with react.

- Authors note: no one was trying to ship anything faster, they were trying to make their code base better. I am a huge fan of trying something, versus the perpetual complainer that refuses to do anything without it being the “perfect” architecture or solution.

Still not convinced?

I get it. How about we remove software engineering from the equation all together, and explore an analogy:

- You are preparing dinner for your partner / child / loved one. It is a dish best served and eaten hot, and requires multiple items cooking or baking at once. (these are the requirements!)

- Washing every dish as you go is impractical, and will likely result in burned or mis-timed food. Washing the dishes right after the meal is plated will result in a poor experience and taste. (these are the constraints!)

- So, what you do is put all the pots, pans, spatulas, knives and bowls in the sink as you are finished with them. (this is the borrowing of debt!)

- You enjoy your meal with those present, and are applauded for your efforts (this is shipping it!)

- After dinner, you have a branching choice…

- You add your plates and utensils to the dish pile in the sink and think to yourself “I’ll clean this up in the morning. It’s late and I want to watch some Parks and Rec.” (this is the accrual of interest / debt!)

- You bite the bullet and wash all the various dishes in the sink. Geez, haven’t they heard of “I cook, you clean??” (this is the repayment!)

- If you picked choice 1, you are now accruing debt, because even though you intentionally took a shortcut to ship dinner sooner in both cases, you didn’t pay down the debt afterwards. You let the cheese harden to the plates, the sauce stain the plastic bowls, any water leftover in the bowls ferment over night. Yikes, this will now be 10x harder to clean in the morning than if it was shortly after eating the meal.

But wait, there’s more!

So you’ve read this far, meaning you haven’t given up on my rambling tirade (maybe the dinner analogy convinced you to stay? let me know in the comments, and don’t forget to like and subscribe) — “When are they getting to fireworks factory!!?!?” comes to mind (iykyk). Let’s wrap this up with some key takeaways:

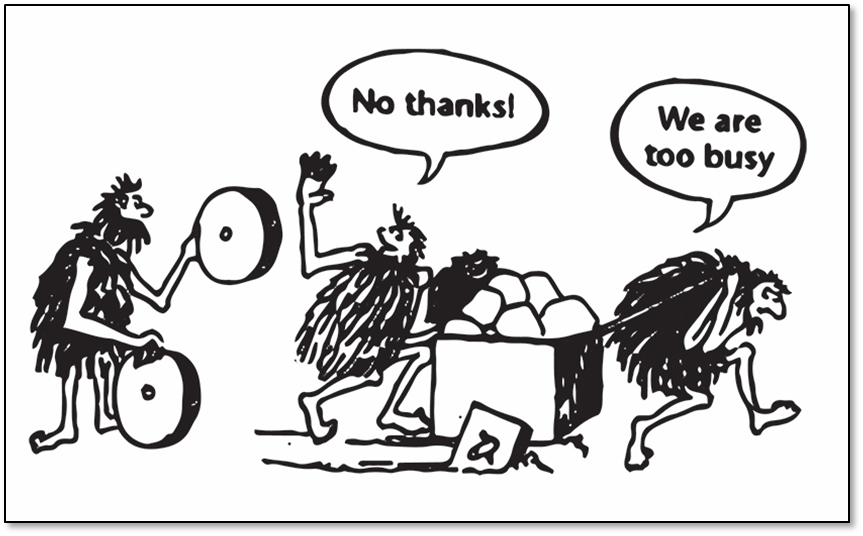

So why is technical debt so common? Well, to answer this, we only need to look at the entirety of human existence: how can we squeeze the most amount of value out of the lowest energy expenditure. Like the rip-roaring late 90s, money can be cheap to borrow — or in our case, code: fragile, but quick to market code is easy and cheap to write. To be fair, it always seems easier and faster when you don’t have hindsight telling you that thing you smelled during development wasn’t an old sandwich, but the lack of foresight around that new feature that “just had to get out the door”.

How can it used for ‘good’ instead of ‘evil’? Debt is fantastic when used properly, it can save someone from not making payroll, or having a roof over their head before a storm. It just comes around to paying it back. When Engineering and Product are trying to gauge value in a new feature that doesn’t have an immediate tell or analytics, it can be very valuable to “just get something out there” and then determine. The kicker here is actually going back and refactoring / redesigning / removing said feature. There needs to be a commitment from both sides of the org that shipping this feature carries risk — both from it potentially flopping (mitigated by speed of delivery) or needing to go back and do it right afterwards (mitigated by more understanding of the feature).

So in conclusion… (where the heck is he going with this??)

Convincing others of its necessity In my years as a senior+ engineer I realized two key things: “nothing will ever be perfect, so don’t let perfect be the enemy of great” and “nothing great is achieved in a silo — accomplishments and failures are shared between people”. It’s our job as engineers to build what the business needs, not what we want. Being a good engineer means finding solutions that match as closely as possible with everyone’s requirements, and sometimes that means incurring some debt to do so. It helps to have a well defined working agreement with the business on this matter, of course. That’s where relationship building and a good leadership team / values come in. The other teams understand that if we build brittle features, everything else takes longer, so they are also incentivized to make compromises in the form of paying debt down after, removing scope, lengthening deadlines, etc.

Side note for another day (blog?): we can complain all day that we work too much on new feature dev and that we don’t get to “pay more debt down”, but that’s on US, not the business. It is our job as an engineering team to own our code / infrastructure and constantly be asking “is there a better way to do this?” The most effective change (almost) always comes from within…